PUNK MUSIC AND SOCIAL CRITICISM IN INDONESIA. THE CONTROVERSY OF THE SONG BAYAR BAYAR BAYAR AND THE INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSE

MÚSICA PUNK Y CRITICA SOCIAL EN INDONESIA: LA POLÉMICA DE LA CANCIÓN BAYAR BAYAR BAYAR Y LA RESPUESTA INSTITUCIONAL

Dedy Afriadi

Institut Seni Budaya Indonesia Aceh

Benny Andiko

Institut Seni Budaya Indonesia Aceh

DOI: 10.33732/ASRI.6859

.........................................

Recibido: (31 07 2025)

Aceptado: (25 10 2025)

.........................................

Cómo citar este artículo

Afriadi, Dedy y Andiko, Benny (2025). Punk music and social criticism in Indonesia. The controversy of the song “Bayar Bayar Bayar” and the institutional response. ASRI. Arte y Sociedad. Revista de investigación en Arte y Humanidades Digitales, (29), e6859

Recuperado a partir de https://doi.org/10.33732/ASRI.6859

Abstract

The song Bayar Bayar Bayar by the punk band Sukatani sparked controversy in Indonesia, showing how punk music has become a tool of social criticism of economic policies and structural injustices. This issue is important in the broader discourse on cultural censorship, freedom of expression, and the role of institutions in responding to social criticism through music. This research aims to analyze the meaning of the song's lyrics, public and media reactions, and institutional responses to them. Using a qualitative method with critical discourse analysis, this study examines media texts, audiovisual recordings, and interviews with academics. The results of the analysis show that punk music remains a form of resistance to state hegemony, despite facing censorship and silencing. Thus, the repressive response to music with social criticism strengthens the song's appeal as a symbol of resistance. This study emphasizes the need for more inclusive cultural policies, as well as more open dialogue between artists and institutions to accommodate freedom of expression in public spaces.

Keywords

Punk music, controversy, Bayar Bayar Bayar song, social criticism, indonesian institutions.

Resumen

La canción Bayar Bayar Bayar de la banda punk Sukatani provocó controversia en Indonesia, mostrando cómo la música punk se ha convertido en una herramienta de crítica social de las políticas económicas y las injusticias estructurales. Este tema es importante dentro del discurso más amplio sobre la censura cultural, la libertad de expresión y el papel de las instituciones en la respuesta a la crítica social a través de la música. Esta investigación tiene como objetivo analizar el significado de la letra de la canción, las reacciones del público y los medios de comunicación y las respuestas institucionales a las mismas. Utilizando un método cualitativo y análisis crítico del discurso, este estudio examina textos mediáticos, grabaciones audiovisuales y entrevistas con académicos. Los resultados del análisis muestran que la música punk sigue siendo una forma de resistencia a la hegemonía estatal, a pesar de enfrentar la censura y el silenciamiento. Por lo tanto, la respuesta represiva a la música con crítica social fortalece el atractivo de la canción como símbolo de resistencia. Este estudio enfatiza la necesidad de políticas culturales más inclusivas, así como un diálogo más abierto entre artistas e instituciones para dar cabida a la libertad de expresión en los espacios públicos.

Palabras clave

Música punk, controversia, canción Bayar Bayar Bayar, crítica social, instituciones indonesias.

Introduction

Punk music has long been a medium of resistance to social injustice, with lyrics criticizing economic inequality, corruption, and state repressiveness (Worley, 2020). The controversy of the song Bayar Bayar Bayar by the band Sukatani illustrates the tension between freedom of expression and institutional control over social criticism. In March 2025, the song went viral, exposing economic and bureaucratic injustices that triggered public debate. It reveals how digital platforms in Indonesia amplify social criticism while also becoming new sites of control (Khosravinik & Unger, 2015). This study explores how punk music functions as a vehicle of social advocacy amid political and technological transformations. By analyzing the response of society and the state to criticism in music, this study provides a broader understanding of the dynamics of cultural expression and freedom of expression in Indonesia.

Previous studies (Saputra, 2016; Talmage et al., 2017) have discussed punk as resistance, but they lack analysis of institutional responses and policy implications in Indonesia. This study fills that gap by linking cultural expression, state censorship, and digital activism. Despite studies on music censorship (Kirkegaard & Otterbeck, 2017), few have analyzed specific cases such as Bayar Bayar Bayar that reveal how digital culture shapes institutional responses. This research, therefore, addresses a significant gap by connecting punk resistance, media discourse, and the state’s management of criticism.

The purpose of this paper is to complement the shortcomings of previous studies that have not looked at the problems of Punk Music and Social Criticism in Indonesia: The Controversy of the Song 'Bayar Bayar Bayar' and the Institutional Response in the context of the dynamics of freedom of expression in the digital era and the state's response to social criticism through music. Previous studies have not explored the long-term consequences of repression of vocal musicians, both in terms of the policy landscape, changes in music consumption patterns, and the resilience of the punk community in voicing its criticism. In line with that, this paper answers three main questions: (1) how do the lyrics and theme of the song Bayar Bayar Bayar represent social criticism? (2) How did the public and the media react to the controversy of the song? and (3) how do institutional responses reflect patterns of criticism management in popular culture? Answering these three questions will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between music, social resistance, expression regulation, and public space in Indonesia.

The argument tested in this study is that punk music in Indonesia, especially the song Bayar Bayar Bayar by Sukatani, not only serves as a form of artistic expression but also as a tool of social criticism that triggers diverse institutional responses. The hypothesis put forward is that the sharper the criticism voiced in the lyrics of the song, the more likely it is that there will be a reaction from state authorities, whether in the form of censorship, silencing, or other repressive measures. In addition, this study examines the relationship between the level of public involvement in public discourse through social media and media coverage with the potential escalation of controversy and its impact on freedom of expression. In other words, this paper examines how social criticism in punk music interacts with public and state responses, as well as how these dynamics reflect a broader pattern in the management of institutional criticism in Indonesia.

1. Literature Review

Music Punk

Punk music is a subculture that has developed since the mid-1970s as a form of resistance to social, political, and economic systems that are considered oppressive (Bennett, 2018). In the context of music, punk is characterized by fast tempos, straightforward and provocative lyrics, and a DIY (do-it-yourself) aesthetic that rejects the commercialization of the music industry (Pearson, 2020). According to Talmage et al., (2017), punk is not just a genre of music, but also a form of political expression that voices issues of class, social injustice, and state repression. In Indonesia, punk music developed as part of the youth resistance movement against authoritarianism and corruption since the New Order era. (Nugroho & Kistanto, 2021). Nugroho and Kistanto research also maps the historical context of punk music development in Indonesia, particularly through Aik experiences in the Surabaya scene in the late 1990s, reinforced by references to bands, events, and the community ecosystem. Furthermore, the article successfully demonstrates the close relationship between punk music and zines as ideological media, enabling readers to understand that zines are not merely complementary but an integral part of punk music practices. This article reveals the ideological transformation within the Indonesian punk scene—from radical secular punk to Islamic punk—as a unique phenomenon that distinguishes it from the development of punk in the West. Punk music's outspoken characteristic of criticizing social conditions makes it an effective tool for voicing public discontent, despite often dealing with repressive responses from the state and negative stigma from society (Kitts, 2017). Thus, punk can be understood as a cultural expression that is closely related to political and social struggles.

In various cases, punk music often sparks controversy due to its sharp and bold lyrics. In the UK, bands such as The Sex Pistols came under heavy criticism after releasing the song God Save the Queen, which criticized the monarchy and was eventually banned from being shown on some platforms (Kristiansen, 2018). In the United States, the Dead Kennedys also faced legal resistance over their album that offended the country's political policies (Quail, 2021). Meanwhile, in Indonesia, punk has long been the subject of social control and state repression, as happened to the punk community in Aceh who were arrested and forcibly shaved by the authorities in 2011 (Ashari, 2022). Another more recent case is the controversy of the song Bayar Bayar Bayar by Sukatani, which reaped pros and cons in the public space due to sharp criticism of the government's economic policies. These examples show that punk music was not only a means of expression, but also part of a social resistance that often clashed with state authorities.

Controversy

Controversy is a condition in which there are sharp differences of opinion in society about a certain issue, often triggering public debate and institutional responses (Zimmerman & Robertson, 2017). In social studies, controversy can be understood as the result of conflicts of values, interests, and power that intersect in the public sphere (Özkaynak et al., 2023). According to Mesoudi, (2016), controversy in popular culture often arises when a work of art or cultural expression challenges dominant norms or offends the ruling authority. Controversy in music, in particular, can be sparked by provocative lyrics, strong symbolism, or perceived social criticism (Stoikiv, 2021). Punk music, as a medium of political and social expression, is often a source of controversy because it contains messages that directly challenge state policies, social authorities, or the practices of capitalism (Denisova & Herasimenka, 2019). Thus, controversy in music is not just an artistic polemic, but also a reflection of social and political tensions in society.

Controversial cases in music have occurred in various countries, reflecting how artwork can spark public debate and institutional responses. In the United States, the song Cop Killer from Body Count (1992) drew criticism from police officers and politicians for inciting violence against the police, which eventually forced record labels to withdraw the song from the market (Grow, 2023). In Russia, Pussy Riot faces jail time after staging anti-Putin protests in the form of a music performance at a church, which sparked a backlash from the government and the Russian Orthodox Church (Nemtsova & Walker, 2013). In Indonesia, controversial cases involving punk music have taken many forms, including concert bans and negative stigma against the punk community (Baiti & Gustaman, 2023). The controversy of the song Bayar Bayar Bayar from Sukatani shows a similar pattern, where the social criticism they voice through the lyrics of the song provokes a pro and con response from the community and state institutions. This shows that the controversy in punk music is not only related to freedom of expression, but also the dynamics of power and social control in public spaces.

Indonesian Institutions

Institutions in social and political contexts are defined as social structures or mechanisms that regulate the behaviour of individuals and groups in society (Banaji et al., 2021). In Indonesia, institutions include various entities, ranging from government institutions, law, media, to civil society organizations, that have a role in controlling, supervising, or responding to various social expressions, including music as a medium of criticism (Lambin & Thorlakson, 2018). According to Kostova et al., (2020), institutions work through three main pillars: normative (law and policy), normative (values and morals that prevail in society), and cognitive (perception and social construction). In this context, institutions in Indonesia play an important role in shaping public discourse, both through repressive measures such as censorship and banning, and through dialogue mechanisms that allow social criticism to be accommodated in a wider space. Thus, institutions serve not only as social controllers but also as an arena where various interests fight in the dynamics of freedom of expression.

Cases involving institutions in responding to artistic expression in Indonesia show a pattern of intervention that varies, depending on the level of criticism voiced and the political context surrounding it. During the New Order period, music that was considered subversive often faced strict censorship from the government, as experienced by musicians such as Iwan Fals, whose songs were banned for containing criticism of the government (Meilinda et al., 2021). Post-Reformation, although freedom of expression was more open, institutional control remained present in the form of social pressure, concert bans, and censorship of content deemed provocative (Icha & Puspa, 2024). The controversial case of the song Bayar Bayar Bayar from Sukatani shows how institutions in Indonesia still have a tendency to respond to social criticism with silence or negative labelling actions against groups that are considered to challenge the status quo (Junius Fernando et al., 2022). This reflects the tension between freedom of expression and institutional efforts to maintain social stability and control over public narratives.

2. Method

The unit of analysis in this study is the song Bayar Bayar Bayar from the band Sukatani as a medium of social criticism of corrupt practices in Indonesian police institutions. The focus of this study is the meaning of the lyrics that reflect the public's dissatisfaction with the abuse of power as well as the institutional response that emerged after the song went viral. This song describes how punk cultural expression serves as a tool to voice people's unrest against a system that is considered unfair. The study also explores how institutions respond to criticism conveyed through music, including the pressure on freedom of expression in the context of state regulation. Using a qualitative approach, this study examines song texts and public reactions to understand the dynamics between art, politics, and institutional policy in Indonesia's social space.

This research employs a qualitative case study approach using critical discourse analysis (cda). The design enables a deep interpretation of the song’s lyrics, social context, and the reactions of key stakeholders, including musicians, audience members, journalists, and institutional representatives. Data were collected from multiple sources lyrical texts, media reports, and online discussions complemented by ten in-depth interviews (n=10) with informants selected through purposeful sampling. Participants included musicians, academics, and media practitioners directly involved in the punk scene or music censorship discourse. Inclusion criteria were: (1) active engagement in punk-related culture or discourse; (2) awareness of the Sukatani case; and (3) willingness to participate in an interview. Exclusion criteria involved limited knowledge or indirect participation in the issue.

This study uses a variety of information sources, including text from newspapers, online news, and audio-visual materials, to understand the dynamics of the Bayar Bayar Bayar song controversy in the context of social criticism and institutional responses. These sources were chosen because they provide diverse perspectives, both from the perspective of the media, government, and the wider community, allowing for a more comprehensive analysis. Data from online news and newspapers help uncover how the media frames the issue, while audio-visual recordings, such as interviews or discussions on social media, provide insight into how audiences interpret and respond to the song. This information was then analyzed qualitatively to identify narrative patterns, evolving arguments, and communication strategies used by various actors in response to the social criticism raised through punk music.

This study uses qualitative data analysis with an interpretive approach to understand the meaning contained in the controversy of the Bayar Bayar Bayar song and the institutional response to it. This approach was chosen because it was able to reveal the social, political, and cultural dynamics behind the reaction to punk music as a form of social criticism. The data that has been collected through document analysis, media observations, and interviews are categorized based on key themes, such as criticism of economic policies, repression of artistic expression, and public response. Furthermore, data were analysed using discourse analysis methods to identify rhetorical patterns in the media, institutions, and punk communities. With this method, research can uncover the relationship between song lyrics, political messages, as well as how institutions respond to musical expressions that challenge the status quo.

3. Results

Punk Music as a Social Critique

Punk music is known as a form of expression of dissatisfaction and protest against social norms. In the context of the song Bayar Bayar Bayar, the social criticism presented focuses on the issue of injustice in a system that requires the people to continue to work and pay various obligations without any attention to their welfare. Lyrics that repeat the word “pay” describe a situation where people are stuck in consumptive routines and drowned in financial burdens, while the existing system provides no real solutions or changes. Through sharp lyrics and energetic rhythms, the song invites listeners to realize the injustices that exist in socio-economic structures that only benefit a few people and keep society trapped in an endless cycle. This song not only reflects complaints but also calls for change against the injustices that occur.

Research development

1. Punk music as a social critique: Lyrics of the song Pay Bayar Bayar

Want to make a driving license (pay the police)

Get a ticket on the road (pay the police)

Big motorbike touring (pay the police)

The public transport wants to stop (pay the police)

Oh my, I don't have any money.

To be able to pay the police

Want to make gigs (pay the police)

Report lost items (pay the police)

Go to jail (pay the police)

Get out of jail (pay the police)

Oh my, I don't have any money.

To be able to pay the police

Want to be corrupt (pay the police)

Want to evict the house (pay the police)

Want to clear the forest (pay the police)

Want to be a police officer (pay the police)

Oh my, I don't have any money.

To be able to pay the police

Sukatani, Bayar Bayar Bayar, 2025. Source: https://lirik.id/lyric/bayar-bayar-bayar-sukatani

The song Bayar Bayar Bayar by the band Sukatani has become a hot topic on social media, along with mass demonstrations carried out in various regions of Indonesia. This song is considered controversial because it contains criticism of an institution in Indonesia. Sukatani does not violate any rules when criticizing a social phenomenon. As a work of art, this should be appreciated. The criticism of the song can also be used as input that can be fuel for institutional improvement. The song Bayar Bayar Bayar performed by the band Sukatani became a hot topic in the community. This song raises the issue of alleged illegal levy practices by police officers, thus attracting the attention of various parties, including the police themselves. After going viral on social media, this song sparked a debate about freedom of expression and limits on criticizing public institutions.

Punk music functions as a medium of social criticism of the injustices that occur in society. Its straightforward and energetic characteristics allowed punk to voice dissatisfaction with a system that was perceived as oppressive. The song Sukatani Bayar Bayar Bayar explicitly criticizes economic exploitation and social injustice, as reflected in the lyrics that highlight the financial pressures caused by a system that demands continuous payments without considering the conditions of the small people. The lyrics reflect the experience of the working class burdened by the rising cost of living, as well as their inability to break out of the cycle of economic exploitation. In addition, the use of repetitive words in songs reinforces the nuances of despair felt by the community towards an economic system that is not in their favour. With a direct and unpretentious approach, punk music, including this song, has become not only a form of artistic expression, but also a tool of resistance against a system that is considered oppressive. This shows that punk has an important role in building social awareness through sharp and easy-to-understand criticism.

The song Sukatani Bayar Bayar Bayar represents the typical spirit of resistance of punk music in criticizing social issues, especially economic inequality and financial pressure of working-class people. Punk music is known as a medium of expression that defies social injustice through straightforward, repetitive, and emotional lyrics, which are in line with the song's character in highlighting the oppressive economic realities. The lyrics of the song that constantly mention the word “pay” repeatedly create a psychological effect that illustrates the saturation and helplessness of the community towards an economic system that demands endless payments. In addition, punk music often uses simple tones and fast rhythms to reinforce the message of protest, as heard in this song, which features repetitive patterns and vocal pressure that affirms people's grievances. The anti-establishment attitude in punk is also reflected in the direct and unconvoluted use of everyday language, making clear the criticism of policies that do not favour the small people. Thus, this song not only serves as entertainment, but also as a form of social resistance that is in line with the ideology of punk music.

The Controversy of the Song Pay Paid

Sukatani's song Bayar Bayar Bayar sparked debate in public space because of its lyrics that explicitly criticize the community's economic pressure and policies that are considered burdensome. In the social context, music that voices sharp criticism often provokes mixed reactions, both from musicians, artists, the media, and the wider community, because it can arouse collective awareness of the issues raised. The response to this song also varied, ranging from public support who felt represented by the lyrics, to criticism from those who considered it a form of provocation against the existing system. Some media outlets covered this phenomenon by highlighting how the song became a symbol of the economic unrest of the small people, while on social media, a debate developed between those who considered it a form of freedom of expression and those who felt it could cause social instability. Public online advocacy also strengthened for Sukatani (Figure 1). Not a few parties also support this song as an advocacy tool, considering that music has often been an effective means of protest in the history of social movements. Thus, this controversy reflects how art, especially music, can be a catalyst for debate and social awareness in society.

Figure 1: Swara Retorika. (February 24, 2025).

Source: Instagram@swararetorika

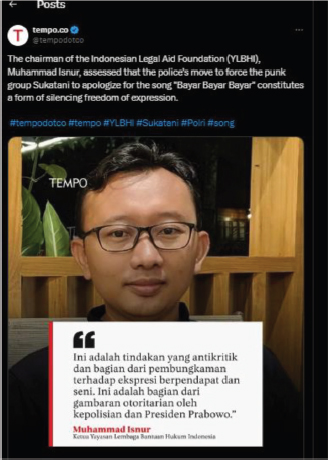

The song Bayar Bayar Bayar popularized by Sukatani has caused controversy among the public, but many netizens have expressed support for Sukatani on social media. This controversy arose because the song's lyrics were considered satirical and had the potential to spark public debate. However, freedom of expression is a right guaranteed by the constitution, as stated by the Commissioner of the National Police Commission, Choirul Anam (Figure 2). This right provides space for every individual to express his or her views and opinions without fear of being punished or restrained. In the case of this song, although some parties consider the lyrics controversial, there is no obvious violation of the law. This assessment was strengthened by the positive attitude shown by many social media users who supported Sukatani, who considered that the song was just a form of freedom of expression in a democratic society. Muhammad Isnur, Chairman of the Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation, assessed that the police's move to force the punk group Sukatani to apologize was a form of silencing freedom of expression (Figure 3). Therefore, this controversy can be seen as a test for democracy and freedom of expression in Indonesia.

Figure 2: National Police Commission. (March 1, 2025).

Source: Tiktok @yogisaputra7152

Figure 3: Chairman of the Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation (YLBHI) Muhammad Isnur. (February 21, 2025).

Source: X @tempo.co

The controversy of the song Sukatani Bayar Bayar reflects how music can trigger debate in the public space related to social issues. In the context of society, artworks that contain social criticism often elicit mixed responses, depending on the perspective and interests of each party. The song received support from people who felt that the lyrics reflected the reality of their lives but also faced criticism from those who considered it too provocative. The media played an important role in framing this debate, with various news reports highlighting both the musicality and social impact aspects of the song. On social media, discussions about the song are growing rapidly, showing differences of opinion between those who consider it a form of freedom of expression and those who think it can trigger social instability. Some have even proposed restrictions or bans on the dissemination of this song, although many have resisted on the grounds of artistic freedom. Thus, this controversy shows that music is not just entertainment but also has the power to influence public opinion and social dynamics.

Institutional response to songs and social criticism

The institutional response to Sukatani's song Bayar Bayar Bayar reflects the dynamic between freedom of expression and control over social discourse in public spaces. In many cases, artwork containing social criticism often faces censorship efforts or repressive measures from authorities who feel that the message in the song could disrupt social stability. Some reports mention pressure on the song's distribution, including potential bans on broadcasting or restrictions on access on various platforms. In addition, legal discourse has also emerged, with the possibility that the lyrics of this song are considered to violate certain provisions related to provocative public speech. However, the punk audience and community, which has historically had a tradition of resistance to repression, responded by defending freedom of expression and condemning any form of silencing of social criticism. Discussions on social media and public spaces show the community's solidarity with the Sukatani band, emphasizing that music remains a powerful advocacy tool. Thus, this phenomenon highlights the tug-of-war between authority and artistic freedom in conveying the social realities faced by society.

The National Police Chief appointed the band Sukatani as National Police ambassadors (Figure 4) following the viral popularity of the song Bayar Bayar Bayar. This move aims to increase criticism and input on the National Police and prevent deviant behavior among police officers. The National Police Chief emphasized that the National Police is open to criticism for the sake of institutional improvement and good relations with the public. The band Sukatani withdrew their song Bayar Bayar Bayar and apologized to the Indonesian National Police after it went viral. The song was seen as criticizing police officers who abuse their power. The National Police Chief stated that he was not against criticism and appointed the band as ambassadors, demonstrating positive changes in democracy in Indonesia. A healthy democracy requires laws that function to uphold democratic values. Without functioning laws, people will struggle to think and express themselves freely. Statements from the Sukatani band, admitting to being intimidated and rejecting an offer to become Police Ambassadors (Figure 5). This Issue entered mainstream public debate through national talk shows (Figure 6).

Figure 4: Not Labeled Anti-Criticism, the National Police Chief Invites the Sukatani Band to Become the National Police Ambassador After the “Pay Your Bill” Polemic. (February 23, 2025).

Source: Youtube Tribunnews

Figure 5: Five Latest Statements of the Sukatani Band, Admitting Being Intimidated and Refusing the Offer to Become a Police Ambassador. (March 2, 2025).

Source: Youtube TribunJakarta Official.

Figure 6: Indonesia Lawyers Club: The Song Bayar Bayar Bayar Testing Democracy. (February 23, 2025).

Source: Youtube ILC.

The tension between authority control and freedom of expression in social criticism is shown from the institutional response to the song Sukatani Bayar Bayar Bayar. In many cases, artworks containing messages of resistance often face repressive measures, either through censorship, bans, or legal threats, aimed at limiting the spread of messages deemed to be disruptive to social stability. This phenomenon is also seen in the effort to silence the Sukatani band, with the emergence of debates regarding the discourse on banning songs and the potential legal consequences for the lyrics they perform. On the other hand, several cultural institutions, music institutions and supporters of freedom of expression responded by defending the band, rejecting all forms of repression, and asserting that art must remain a space for social criticism. Discourse on police ambassadors also emerged in public discussions, showing institutional strategies in responding to the dynamics between authorities and society. Thus, this phenomenon confirms that music is not only a means of entertainment, but also a political and social tool capable of arousing awareness and triggering complex institutional responses.

The institutional response to the song Sukatani Bayar Bayar Bayar reflects the tension between freedom of expression and state control in social, legal, political, and economic aspects. Socially, this song sparked public discussion about economic inequality and financial pressures experienced by the lower class, thus gaining support from the community that felt represented by its critics. From a legal point of view, the emergence of censorship discourse and legal threats against the Sukatani band shows how regulations can be used as a tool to silence criticism of economic policies. Politically, institutional responses such as the discourse of police ambassadors can be seen as a strategy to quell protests by shaping a counter-narrative that is more favorable to the government. From an economic perspective, the song reflects people's anxiety about a system that burdens them with sustainable financial obligations, making it a symbol of resistance to policies that are perceived as not on the side of the small people. Thus, this phenomenon shows that music not only functions as entertainment, but also as a tool of social criticism that is able to influence legal, political, and economic discourse more broadly.

Discussion

This study examines the role of punk music as a medium of social criticism in Indonesia through the analysis of the song Bayar Bayar Bayar by Sukatani. The song highlights the practice of illegal levies and bureaucratic corruption, which then sparked widespread controversy in the public sphere. The findings show that while Bayar Bayar Bayar received massive public support as an expression of free speech, it also faced institutional attempts to discipline and reappropriate criticism. This reflects what Foucault calls a “technology of power,” which is here countered by music as a “technology of resistance”(Waller, 2018). Institutional responses ranging from reprimands to co-optation through symbolic gestures like the police ambassador offer demonstrate a strategy of “domesticating dissent”, as well as the dismissal of the band's vocalist from his job. Public debate on social media and media reports have strengthened the song's position as a symbol of resistance to injustice. International comparisons show that similar patterns emerge elsewhere: in the UK, The Sex Pistols’ God Save the Queen challenged Monarchy (Street et al., 2018); in Russia, pussy riot used music to confront political repression (Amico, 2016); and in Latin America, protest music remains central in debates over democracy and cultural control (Ritter, 2023). These parallels position Indonesia within a broader global context of cultural resistance. The study reveals that punk music remains an effective means of critiquing social reality, despite the face of silence. This case reflects the challenges of freedom of expression in Indonesia and the need for a more open space for social criticism through art.

The results of this study show that punk music in Indonesia remains an effective tool of social criticism despite facing institutional pressures. The controversy of the song Bayar Bayar Bayar confirms the theory that music as a form of cultural expression can be a threat to the power structure it criticizes (Chen, 2024). The repressive actions against Sukatani reflect the pattern of the state's response to criticism that is considered subversive, as has happened in the case of protest music in various countries (Denisova & Herasimenka, 2019). In addition, the widespread public reaction indicated that the song succeeded in arousing social awareness, in line with the concept of “music as a medium of mobilization” in social movements (Sakakeeny, 2024). This case also shows the tug-of-war between freedom of expression and state control, considering the history of music censorship in Indonesia that is still ongoing until the digital era (Hansen, 2012). Thus, this study confirms that punk music remains relevant as a medium of social resistance.

The results of the study also confirm that punk music in Indonesia is not just an artistic expression, but a representation of resistance to social injustice and institutional control. In historical contexts, protest music has been part of a global social movement, such as 1970s-era punk in Britain that opposed capitalism and state repression (Johnston, 2016). In Indonesia, a similar pattern has been seen since the New Order, when music was often used as a political expression tool against authoritarianism (Caiani & Padoan, 2023). The controversy of the song Bayar Bayar Bayar shows that although reforms have brought greater freedom, control over social criticism through music still applies. From a theoretical perspective, art can be understood as a technology of resistance (Frers & Meier, 2017), in which cultural practice produces counter-discourses against censorship. This framework explains how punk in Indonesia reinvents itself through digital spaces, turning censorship into a site of new political visibility. Therefore, punk music remains a symbol of resistance to ideological domination in Indonesia.

The exploration of paid songs has important implications for the understanding of freedom of expression and institutional responses to social criticism in Indonesia. Functionally, punk music has proven to remain an effective forum for society to articulate dissatisfaction with corrupt bureaucratic policies and practices (Williams, 2019). The song Bayar Bayar Bayar acts as a catalyst for social awareness, strengthening public discourse on illegal levies and structural injustice. However, dysfunctionally, the repressive response to Sukatani suggests that the state still maintains a control mechanism against criticism through the arts, which has the potential to limit creativity and freedom of speech. In addition, this kind of silencing can create a deterrent effect for other musicians who want to raise similar issues. Therefore, this study confirms the need for more progressive policies in protecting artistic expression as part of a healthy democracy (Jost et al., 2022).

This study reinforces previous research that highlighted music as a tool of social resistance. Hebdige in Subculture: The Meaning of Style explains that punk is a form of expression of opposition to the dominant structure, in line with the function of the song Bayar Bayar Bayar as a critique of the corrupt bureaucracy (Sklar et al., 2022). Sandoval's research also found that music in Indonesia is often a means of protest, such as the case of Iwan Fals who faced censorship and political pressure in the New Order era (Sandoval, 2016). However, in contrast to their research that focused on folk and pop music, this study shows that punk remains an effective means of protest in the digital age. Moreover Keh-Nie Lim & Zhang, (2023) notes that music censorship in Asi tends to be structural, while the findings in this study reveal a new dynamic, namely the role of social media in strengthening and limiting the spread of social criticism songs. Thus, this study highlights the transformation of resistance mechanisms in the Indonesian punk music landscape.

Based on these findings, concrete steps are needed to ensure that freedom of expression in music remains guaranteed without neglecting fair regulation. First, the government must revise censorship policies and art regulations so that they are not used as a repressive tool against social criticism. This policy must refer to the standards of human rights and freedom of expression as stipulated in the 1945 Constitution and Law No. 39 of 1999 concerning human rights. Second, the punk music community and cultural activists need to strengthen advocacy networks so that cases like Sukatani's do not recur, for example by building cross-genre solidarity and collaborating with legal institutions. Third, the use of social media must be maximized as an alternative space to spread social criticism more widely. With these measures, punk music can continue to be a legitimate voice of resistance and contribute to more democratic social change.

Conclusion

This research confirms that music is not just an artistic expression, but also an important medium in articulating social criticism and resistance to injustice. The Bayar Bayar Bayar case shows that even though Indonesia has undergone a democratic transition, the space for freedom of expression still faces challenges from regulations that are not always in favour of artists. The main lesson that can be learned is that punk music remains relevant as a tool of social advocacy, especially in the digital age where the spread of messages is getting wider and faster. In addition, institutional responses to criticism in the arts reflect the dynamics of the relationship between the state and civil society, which are constantly changing according to the political and social context. Therefore, a deeper understanding of music as a form of protest can be the foundation for fighting for more democratic policies in support of freedom of expression and artists' rights in Indonesia.

This research makes an important contribution to the study of music and social criticism in Indonesia by presenting empirical data on public and institutional responses to the song Bayar Bayar Bayar. Scientifically, this study enriches the discourse on punk music as a medium of protest by highlighting how the dynamics of resistance in music develop in the digital era. The approach used also offers a new perspective by combining lyric analysis, media reactions, and institutional responses, resulting in a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between music, policy, and public space. In addition, this study opens new questions about the extent to which freedom of expression in art can survive amid increasingly strict regulations. Thus, this study not only reinforces previous theories about music and resistance but also encourages further exploration of the role of music as a tool of social advocacy in Indonesia.

This research has several limitations that need to be considered for further study development. First, the focus of this study is more on the response to the song Bayar Bayar Bayar from a public and institutional perspective, but it has not explored in depth the perspectives of music industry players, such as record labels, digital distributors, and the media. Second, the analysis in this study is limited to one specific case, so generalizations to the dynamics of punk music in Indonesia still need to be expanded with comparative studies of other bands or songs that have similar social criticism content. Third, the approach of this research is still based on qualitative analysis, while quantitative studies that measure the impact of songs on changes in public opinion or policies have not yet been carried out. Therefore, further research is recommended to explore these aspects to produce a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between music, social protest, and regulation in Indonesia.

Bibliographic references

Amico, S. (2016). Digital Voices, Other Rooms: Pussy Riot’s Recalcitrant (In)Corporeality. Popular Music and Society, 39(4), 423–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2015.1088284

Ashari, D. F. (2022). Identitas Komunitas Punk di Aceh: Sebuah Kajian Historis. Syntax Literate; Jurnal Ilmiah Indonesia, 7(1), 537. https://doi.org/10.36418/syntax-literate.v7i1.5728

Baiti, N. N., & Gustaman, F. A. (2023). Respon komunitas punk terhadap stigma dari masyarakat (studi kasus di Kecamatan Cepu, Kabupaten Blora). Journal of Indonesian Social Studies Education (JISSE), 1(2), 200–208.

Banaji, M. R., Fiske, S. T., & Massey, D. S. (2021). Systemic racism: individuals and interactions, institutions and society. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 6(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-021-00349-3

Bennett, A. (2018). Conceptualising the Relationship Between Youth, Music and DIY Careers: A Critical Overview. Cultural Sociology, 12(2), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975517750760

Caiani, M., & Padoan, E. (2023). Conclusion: Challenges and Opportunities of (Pop) Music for Populism. In Populism and (Pop) Music. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-18579-3_7

Chen, D. (2024). Seeing Politics Through Popular Culture. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 29(1), 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-023-09859-x

Denisova, A., & Herasimenka, A. (2019). How Russian Rap on YouTube Advances Alternative Political Deliberation: Hegemony, Counter-Hegemony, and Emerging Resistant Publics. Social Media + Society, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119835200

Frers, L., & Meier, L. (2017). Resistance in Public Spaces: Questions of Distinction, Duration, and Expansion. Space and Culture, 20(2), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331217697105

Grow, K. (2023). Ice-T and the Controversial History of Body Count’s ‘Cop Killer’: ‘Maybe You Should Be Scared.’ RollingStone. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/body-count-cop-killer-ice-t-book-excerpt-1234876409/

Hansen, E. (2012). Freedom of expression in distributed networks. TripleC. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v10i2.450

Icha, R., & Puspa, S. H. (2024). Indonesia: Censorship of artistic works usually only occurs under authoritarian regimes says Amnesty. Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières. https://www.europe-solidaire.org/spip.php?article73212

Johnston, H. (2016). Dimensions of Culture in Social Movement Research. In The SAGE Handbook of Cultural Sociology (pp. 414–428). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473957886.n30

Jost, J. T., Baldassarri, D. S., & Druckman, J. N. (2022). Cognitive–motivational mechanisms of political polarization in social-communicative contexts. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(10), 560–576. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-022-00093-5

Junius Fernando, Z., Pujiyono, Rozah, U., & Rochaeti, N. (2022). The freedom of expression in Indonesia. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2022.2103944

Keh-Nie Lim, C., & Zhang, M. (2023). Chinese national music platformisation: A systematic review. Heliyon, 9(11), e22304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22304

Khosravinik, M., & Unger, J. W. (2015). Critical Discourse Studies and Social Media: power, resistance and critique in changing media ecologies. In Methods of critical discourse studies.

Kirkegaard, A., & Otterbeck, J. (2017). Introduction: Researching Popular Music Censorship. Popular Music and Society, 40(3), 257–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2017.1307656

Kitts, T. M. (2017). The Politics of Punk: Protest and Revolt from the Streets. Popular Music and Society, 40(1), 118–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2017.1270538

Kostova, T., Beugelsdijk, S., Scott, W. R., Kunst, V. E., Chua, C. H., & van Essen, M. (2020). The construct of institutional distance through the lens of different institutional perspectives: Review, analysis, and recommendations. Journal of International Business Studies, 51(4), 467–497. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-019-00294-w

Kristiansen, L. J. (2018). “Not My President”: Punk Rock and Presidential Protest from Ronald to Donald. In In You Shook Me All Campaign Long: Music in the 2016 Presidential Election and Beyond (pp. 51–88). University of North Texas Press. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/172/edited_volume/chapter/2379516

Lambin, E. F., & Thorlakson, T. (2018). Sustainability Standards: Interactions Between Private Actors, Civil Society, and Governments. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 43(1), 369–393. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-102017-025931

Meilinda, N., Giovanni, C., Triana, N., & Lutfina, S. (2021). Resistensi Musisi Independen terhadap Komodifikasi dan Industrialisasi Musik di Indonesia. Jurnal Komunikasi, 16(1), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.20885/komunikasi.vol16.iss1.art6

Mesoudi, A. (2016). Cultural Evolution: A Review of Theory, Findings and Controversies. Evolutionary Biology, 43(4), 481–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11692-015-9320-0

Nemtsova, A., & Walker, S. (2013). Freed Pussy Riot members say prison was time of “endless humiliations.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/dec/23/freed-pussy-riot-amnesty-prison-putin-humiliation

Nugroho, F. A., & Kistanto, N. H. (2021). Gerakan Melawan Arus melalui Karya Sastra: Kajian Sosiologi Sastra. KREDO: Jurnal Ilmiah Bahasa Dan Sastra, 5(1), 336–353. https://doi.org/10.24176/kredo.v5i1.6861

Özkaynak, B., Muradian, R., Ungar, P., & Morales, D. (2023). What can methods for assessing worldviews and broad values tell us about socio-environmental conflicts? Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 64, 101316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2023.101316

Pearson, D. (2020). Rebel Music in the Triumphant Empire. In Rebel Music in the Triumphant Empire: Punk Rock in the 1990s United States. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780197534885.001.0001

Quail, B. (2021). American Idiots: Charting Protest and Activism in the Alternative Music Scene During George W. Bush’s Presidency. Comparative American Studies An International Journal, 18(3), 302–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775700.2021.2015219

Ritter, J. (2023). Music, Politics, and Social Movements in Latin America. Latin American Perspectives, 50(3), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X231201636

Sakakeeny, M. (2024). Music, Sound, Politics. Annual Review of Anthropology, 53(1), 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-041422-011840

Sandoval, E. (2016). Music in peacebuilding: a critical literature review. Journal of Peace Education, 13(3), 200–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2016.1234634

Saputra, A. O. (2016). Memahami pola komunikasi kelompok antar anggota komunitas punk di Kota Semarang. Jurnal The Messenger, 4(1), 44–62. https://doi.org/10.26623/themessenger.v4i1.276

Sklar, M., Strübel, J., Freiberg, K., & Elhabbassi, S. (2022). Beyond Subculture the Meaning of Style: Chronicling Directions of Scholarship on Dress since Hebdige and Muggleton. Fashion Theory, 26(6), 715–735. https://doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2021.1954834

Stoikiv, A. (2021). The role of thrash metal in the formation of extreme heavy music (based on the interview of musicians). Scientific Herald of Uzhhorod University. Series: History, 1 (44), 160–168. https://doi.org/10.24144/2523-4498.1(44).2021.232681

Street, J., Worley, M., & Wilkinson, D. (2018). ‘Does it threaten the status quo?’ Elite responses to British punk, 1976–1978. Popular Music, 37(2), 271–289. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026114301800003X

Talmage, C. A., Peterson, C. B., & Knopf, R. C. (2017). Punk Rock Wisdom: An Emancipative Psychological Social Capital Approach to Community Well-Being (pp. 11–38). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-0878-2_2

Waller, C. (2018). ‘Darker than the Dungeon’: Music, Ambivalence, and the Carceral Subject. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law - Revue Internationale de Sémiotique Juridique, 31(2), 275–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-018-9558-9

Williams, J. P. (2019). Subculture’s Not Dead! Checking the Pulse of Subculture Studies through a Review of ‘Subcultures, Popular Music and Political Change’ and ‘Youth Cultures and Subcultures: Australian Perspectives.’ YOUNG, 27(1), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308818761271

Worley, M. (2020). Raymond A. Patton, Punk Crisis: The Global Punk Rock Revolution. Journal of Contemporary History, 55(1), 237–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022009419896481p

Zimmerman, J., & Robertson, E. (2017). The controversy over controversial issues. Phi Delta Kappan, 99(4), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721717745541

BIO

Dr. Dedy Afriadi  is an Indonesian lecturer and art practitioner who is active in the academic, curatorial, and visual arts and culture research of Aceh. She completed her postgraduate education at ISI Yogyakarta and doctoral program at ISI Surakarta, and has participated in various conferences and art activities at the national and international levels. He is also known as an Acehnese traditional music player (seurune kale), researcher, as well as facilitator of various academic trainings that focus on scientific publications and strengthening local cultural values in contemporary art discourse. dedyafriadi@isbiaceh.ac.id

is an Indonesian lecturer and art practitioner who is active in the academic, curatorial, and visual arts and culture research of Aceh. She completed her postgraduate education at ISI Yogyakarta and doctoral program at ISI Surakarta, and has participated in various conferences and art activities at the national and international levels. He is also known as an Acehnese traditional music player (seurune kale), researcher, as well as facilitator of various academic trainings that focus on scientific publications and strengthening local cultural values in contemporary art discourse. dedyafriadi@isbiaceh.ac.id

Benny Andiko  is a lecturer in the Department of Performing Arts, Indonesian Institute of Cultural Arts and Culture Aceh. Completed his S1 education in the Music Arts Study Program and S2 in the Art Creation and Assessment Study Program ISI Padangpanjang. During his academic career, he carried out the Tridharma of Higher Education activities in the development and preservation of traditional arts with the use of technology. In addition, he is also involved in various performing arts events both local, national and international as practitioners, production leaders, stage managers and sound designers. bennyandiko@isbiaceh.ac.id

is a lecturer in the Department of Performing Arts, Indonesian Institute of Cultural Arts and Culture Aceh. Completed his S1 education in the Music Arts Study Program and S2 in the Art Creation and Assessment Study Program ISI Padangpanjang. During his academic career, he carried out the Tridharma of Higher Education activities in the development and preservation of traditional arts with the use of technology. In addition, he is also involved in various performing arts events both local, national and international as practitioners, production leaders, stage managers and sound designers. bennyandiko@isbiaceh.ac.id