THE ROLE OF INTERACTIVITY IN KLAUS OBERMAIER SCENOGRAPHIC SPACES

EL PAPEL DE LA INTERACTIVIDAD EN LOS ESPACIOS ESCENOGRÁFICOS DE KLAUS OBERMAIER

Cristina Barbiani

Università Iuav di Venezia

DOI: 10.33732/ASRI.6880

.........................................

Recibido: (07 10 2025)

Aceptado: (03 11 2025)

.........................................

Cómo citar este artículo

Barbiani, Cristina. (2025). The role of interactivity in Klaus Obermaier scenographic spaces. ASRI. Arte y Sociedad. Revista de investigación en Arte y Humanidades Digitales, (28), e6880.

Recuperado a partir de https://doi.org/10.33732/ASRI.6880

Abstract

This paper examines the role of interactivity in scenographic environments through the analysis of the intermedia dance performances of Klaus Obermaier.

Through systems of real-time motion tracking, computer vision, and body mapping, his work transforms the stage into an interactive device that eliminates the traditional hierarchy between stage, artist, and performer. In this context, interactivity becomes a generative dramaturgical principle, a process of real-time meaning-making that redefines experiences of presence, embodiment, and participation for both dancers and audience.

The analysis situates Obermaier’s practice within the broader discourse on digital scenography and contemporary choreography, arguing that responsive media redefine the terms of the artistic process and the role of the dancers.

Keywords

Digital scenography, interactivity, dance performance, videomapping, Obermaier, real-time motion tracking.

Resumen

Este artículo examina el papel de la interactividad en los entornos escenográficos a través del análisis de las performances de danza intermedia de Klaus Obermaier.

Mediante sistemas de seguimiento de movimiento en tiempo real, visión por computadora y mapeo corporal, su obra transforma el escenario en un dispositivo interactivo que elimina la jerarquía tradicional entre escenario, artista e intérprete. En este contexto, la interactividad se convierte en un principio dramatúrgico generativo, un proceso de creación de significado en tiempo real que redefine las experiencias de presencia, corporeidad y participación tanto para los bailarines como para el público.

El análisis sitúa la práctica de Obermaier dentro del discurso más amplio sobre escenografía digital y coreografía contemporánea, argumentando que los medios responsivos redefinen los términos del proceso artístico y el papel de los bailarines.

Palabras clave

Escenografía digital, interactividad, performance de danza, videomapping, Obermaier, seguimiento de movimiento en tiempo real.

Introduction

In recent decades, the performing arts have undergone a radical transformation through the integration of digital and interactive technologies into the stage. Within this panorama, the figure of Klaus Obermaier (Linz, 1955) occupies a position of absolute prominence: a musician and visual artist, Obermaier has redefined the relationship between body, image, and sound, exploring the potential of the stage as a hybrid space in which physical reality and digitally generated environments in real time interpenetrate.

His works, presented in more than forty countries, constitute crucial milestones in the development of contemporary “intermedia”performance (de Lahunta S., 2008, Mocan R., 2013) With pieces such as D.A.V.E. (1999), Apparition (2004), and Le Sacre du Printemps (2006), Obermaier introduced new forms of real-time interaction between dancers, digital systems, and audiences, challenging the traditional boundaries of choreography and theatricality. It is no coincidence that the international press has described his work as “a milestone in the history of digital arts” (Judmayer, 2006).

In parallel with his artistic production, Obermaier has pursued significant research and teaching activities within academic and institutional contexts, including IUAV University of Venice, IAAC in Barcelona, and the Interactive Arts program at the University of Cluj in Romania. In these settings, he has contributed to advancing a pedagogical approach grounded in interdisciplinarity and in the central role of experimentation through digital and interactive tools.

This article aims to analyze Obermaier’s contribution to creative productions that bring together interactive digital arts and the performing arts, examining the ways in which his works have redefined the concept of stage presence, the relationship between performer and technology, and the perceptual experience of the spectator.

Methodology

The methodology adopted in this research lies at the intersection of technical analysis, research through practice, and qualitative research based on interviews. The investigation begins with a corpus of primary and secondary sources, including the artist’s biography, documentation of the works, international reviews, and articles published in specialised journals and books, which together make it possible to reconstruct the evolution of Klaus Obermaier’s creative artistic process, with a specific focus on dance performances.

Alongside these sources, the research is grounded in direct experience within both academic and performative contexts in which Obermaier has been active. Following his long-standing teaching experience at the Faculty of Design and Arts at IUAV University of Venice, where he was assisted in teaching by the present author, Klaus Obermaier and Cristina Barbiani conceived and coordinated the Master’s program in Interactive Arts (later renamed Master’s in Digital Exhibit) at IUAV University of Venice, where Obermaier taught for several years. This position made it possible to observe from within the pedagogical processes, collaborative dynamics, and modes of transmitting interdisciplinary competences that characterise his practice.

Moreover, between 2010 and 2011, the author took part in the production of the performative project “The Concept of (here and now)”, thereby gaining a privileged perspective on the processual and workshop-based dimension of Obermaier’s work. This direct experience will be further integrated by an interview intended to examine in greater depth both the methodology and the technical strategies employed by the artist, as well as to retrace the decisive steps that, throughout his career, have marked the most significant developments in the field of digital scenography.

Finally, the analysis will be framed within a theoretical framework of studies on the performing and intermedial arts, particularly concerning the concepts of interactivity, mediated body, and hybridisation of languages. The triangulation of documentary materials, direct experience, historical reconstruction, and theoretical reflections will make it possible to elaborate a multilayered reading of Obermaier’s contribution to contemporary performing arts.

Biography

After graduating in Graphic Arts from HTL Linz (Höhere Technische Lehranstalt), Klaus Obermaier continued his music education first at the Bruckner Conservatory in Linz and later at the Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst in Wien, studying classical guitar. In 1984, he was awarded the Konzertdiplom with distinction (Concert Diploma with Distinction) at the Hochschule für Musik und darstellende Kunst (University of Music and Performing Arts) in Vienna. He completed one year of studies at the University of Arts in Linz, then he decided to dedicate completely to music, electric guitar and touring with his band “Open Art Band”. At that time his music references were King Crimson, Frank Zappa and Emerson Like and Palmer, from whom he got the interest in synthesisers in creative electronic music. Although his main interest was music, from the very beginning Obermaier approached his work on stage as a space for visual experimentation. His curiosity about all forms of innovation in the performing arts led him to experiment playfully with lights, lasers, and other technologies available at the time.

Approaching the intermedia dance performance

Between 1988 and 1992, Klaus Obermaier collaborated with various musicians and ensembles, including the Balanescu Quartet, for whom he created his first interactive video projections, as well as with Robert Spour, with whom he began working in parallel on the production of real-time generated visuals for the stage through video projection.

These early experiences demonstrate that for Obermaier, the stage for live music performances was an experimental space where to blend together visual arts, music and technology with no boundaries and curiosity towards collaborations.

In 1992, when he had the opportunity to meet Martino Müller and Nancy Euvrink, both members of the Nederlands Dans Theater, Obermaier realised that the integration of dancers on stage offered an opportunity that further enriched the performance, making it even more compelling.

The collaboration with Müller and Euvrink continued, and the working group composed of the two dancers, Klaus Obermaier, and Robert Spour led to the production of a performance titled “Metabolic Stabilizers” (Figure 1), which premiered at the Bas Gleichenberg Festival in 1994. In this work, of which no video recordings exist but only photographs, Obermaier began experimenting with the superimposition of visual layers onto the dancers’ bodies. In this case, the effect was achieved solely through their passage along an intricate path amid screens on which interactively generated images were projected - images that, thanks to the dancers’ skill to intercept them, gave rise to a performance composed in real time.

Figure 1: Klaus Obermaier. 2004. Metabolic stabilizer. Intermedia dance performance.

Obermaier realised that this was a field he was eager to explore, and the opportunity to develop and go deeper into this approach arose through his encounter with dancer and choreographer Chris Haring, a versatile and inventive member of Nigel Charnock’s renowned group DV8 and later the founder of Liquid Loft.

In 1998, Obermaier’s experiments together with Robert Spour culminated in a production that achieved great success with both audiences and critics. D.A.V.E. premiered in 1998 and continued touring for more than 10 years in 25 countries around the world.

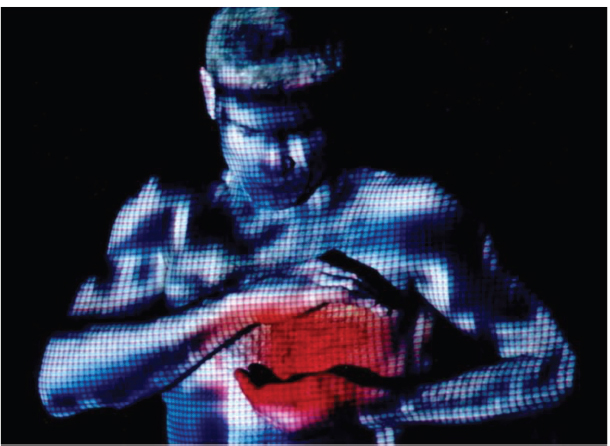

In this work, Obermaier devised a clever technical strategy that employed video projections on the dancers’ bodies. Even before the use of infrared technologies, he sought to simulate a highly precise effect of interactive mapping. In reality, the effect was achieved by playing with visual tricks that mimicked the logic of interactivity, combined with choreography conceived in synergy with the projected images. The result made the images appear interactive, when in fact they were pre-planned and pre-recorded (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Klaus Obermaier. 2004. D.A.V.E. Intermedia dance performance Ph. Marianne Weiss.

A curious detail is that, in order for their bodies to be fully projected upon, the dancers all had to dye their hair very light. The body thus became both scenography and a medium of mediation, playing with the ambiguity of the contemporary body that seeks to overcome the limits of time and aging, as well as the boundaries between genders, dissolving into a stream of digital images that were at times irreverent, at times ironic. D.A.V.E. thus stands as a critical device on the manipulation and transformation of the body through biotechnologies, engaging with the evaporation and dissolution of its boundaries.

In the words of Klaus Obermaier:

One of the most interesting parts in this piece was to work on the transitions between the real body and the body that is just a projection. As everything was happening on stage we worked in a way that you could not really understand what was real and what was digital, and we played a lot with these transitions, especially in D.A.V.E. which was about identity, age, transformation of the body by technology. We tried to make visible these transitions, like a woman becoming a man, becoming old, transforming continuously. And by the fact that this was happening all on stage, the piece became not only a dance piece, it made it also theatrical, even if it was nearly without words. It was invited from a lot of music, theatre, electronic and also puppet festivals, besides the dance festival. (Obermaier, personal communication, 2025)

This element, which would recur frequently in Obermaier’s subsequent works, finds its first articulation here. It prompted the artist to devise ever more innovative ways of constructing intermedia (systems in which the dancer, in synergy with the artist manipulating sound and image in real time, becomes a complex apparatus. In this configuration, not only is there no distinction between different artistic disciplines, but a fusion is also explored between creator and performer, between image and stage, between body and digital material.

The collaboration between Obermaier and Haring continued with a new production in 2001 titled Vivisector, a work that deepened the exploration of the video-technological concept of the moving corporeal projection that had made D.A.V.E. an international success. Vivisector took a further step forward: the focus on video projection as a smart source of light produced a new stage aesthetic in which light, body, video, and acoustic space formed an unprecedented unity. Here, projection light assumed the role of underlining the body and its elements—at times emphasising and multiplying the digital image alongside the physical one, at times, through visual and perceptual solutions, fragmenting and causing parts of the body to disappear. The body was thus continuously broken, cut, and recomposed in a stroboscopic play of light and shadow, which, among other techniques, exploited the ability of bright light to imprint itself on the viewer’s retina and, by contrast, to heighten the surrounding darkness of the auditorium (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Klaus Obermaier. 2001. VIVISECTOR. Intermedia dance performance.

In parallel, Obermaier’s other works led him—through productions such as Maria T (together with the Balanescu Quartet) and Oedipus Reloaded (produced with the support of Ars Electronica)—towards an increasingly intensive use of large-scale rear projections that became ever more interactive, in combination with real-time body-mapped projections, as in one of his most acclaimed and successful works, “Apparition” (Obermaier, K. 2008) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Klaus Obermaier. 2004. Apparition. Interactive dance performance.

This time there is an international team working closely with Obermaier, including London-based dance artists Robert Tannion and Desireé Kongerød and interaction designers and programmers Christopher Lindinger and Peter Brandl (from the Ars Electronica Futurelab). The development of the system for motion tracking and analysis with the infrared camera was provided by Hirokazu Kato from Osaka University in Japan.

As Klaus Obermaier says: “Working inside the environment of the Ars Electronica Futurelab was really effective as any technical problem arose, there was someone that could help to solve the problem.”

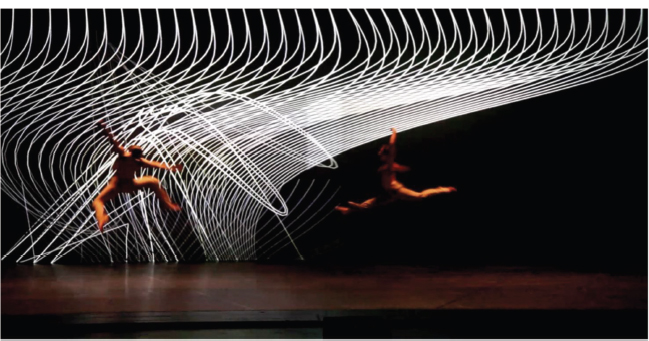

In this work, dancers and choreographers become for the first time performers through movement, which generates the imagery that constructs the interactive scenography in real time. Both, the body mapped images, and the rear projection were controlled by their movements. Computational processes that model and simulate the physics of the real world give life to a kinetic space in which the beauty and dynamics of the human body, together with the quality of its movement, are amplified and transferred into the virtual realm.

As in the project description Obermaier states, “these two main areas of research—the interactive digital system as a performative partner and the creation of an immersive kinetic space—form the artistic backbone of Apparition.” What Obermaier would emphasise today about the creative process, is that there is no hierarchy among the different components of the performance; each discipline was influencing the others from the very beginning.

“Apparition”, as Obermaier describes it:

It was the work that had the biggest impact on the scene. Many artists from a lot of different fields of creativity started to ask me about this piece and moved towards new technology in art because of that. It had a big influence on the dance scene, but also in the interactive arts. Especially the particle system that we used in the end made the ‘particles’ very famous and widely used in performing arts and installations. ((Obermaier, personal communication, 2025)

Here too, the images created on stage produce optical illusions that can only be fully perceived in the live experience. The animations generated by the interactive system create lines that respond to the dancers’ movements, while simultaneously projecting contrasting lines onto their bodies. The dancers transform the background lines, contracting and expanding them with their movement, and at the same time the lines on their body were doing the opposite, creating the perception of depth completely distorted, making the dancers appear as if they were moving to the background.

Another, even more experimental step was taken with the creation of “Le Sacre du printemps”, (Figure 5) an iconic choreography of contemporary dance that has been revisited by more than 200 choreographers, including some of the greatest masters of the twentieth century—from Nijinsky to Béjart, and later Pina Bausch and Mats Ek, to name only a few. The work is described in Klaus Obermaier’s own words as follows:

The epoch prior to World War I, the time in which Stravinsky composed ‘Le Sacre du Printemps’ (The Rite of Spring), was characterized by an ecstatic desire to experience the intensity of life, an emotion that would later mutate into an equally euphoric enthusiasm for war. Logically Stravinsky conceived ‘Le Sacre’ as an orgiastic mass ballet.

The dissolution of social structures is reflected in the dissolution of conventional developments and structures in the composition: Fragmentary, blocklike lining up of movements; abrupt shifts; polytonality and polyrhythm.

This led, together with Nijinsky’s choreography, which translated the composition beat for beat with hectic and complicated movements into dance, to one of the largest premiere scandals of music history.

Now, nearly a hundred years later, the issue of the day is the authenticity of experience in the light of the ongoing virtualization of our habitats. It is the dissolution of our sensuous perception, of the space-time continuum, the fading dividing line between real and virtual, fact and fake, that takes us to the limits of our existence.

The discrepancy between subjective perception and seemingly objective perception produced by stereoscopic camera systems, whose images are filtered and manipulated by computer, constitutes the basis of my staging of ‘Le Sacre du Printemps’.

It is about the immersion of the ‘chosen one’ in virtuality, her fusion with music and space, as an up-to-date ‘sacrifice’ for an uncertain future and as a metaphor for deliverance and for the anticipation of eternal happiness, that new technologies and old religions promise us. Or at least a new dimension of perception.

In addition ‘Le Sacre du Printemps’ brings up for discussion the complex relationship between music, dance and space. In conventional productions of ‘Le Sacre’ one choreographs and dances to the music. In this case, though, the dynamics and structure of the music interactively transform the virtual presence of the dancer and her avatars and thus produce a sort of ‘meta-choreography.’

Stereoscopic projections create an immersive environment, which permits the audience to participate substantially more closely on this communication than in traditional theatre settings.

Stereo cameras and a complex computer system transfer the dancer Julia Mach into a virtual three-dimensional space. Time layers and unusual perspectives overlay one another and multiply themselves, and enable a completely new perception of the body and its sequences of movements. Real-time generated virtual spaces communicate and interact with the dancer. The human body is once more the interface between reality and virtuality.

(Obermaier, personal communication, 2025)

Figure 5: Klaus Obermaier. 2006. Le sacre du printemps. Interactive dance performance.

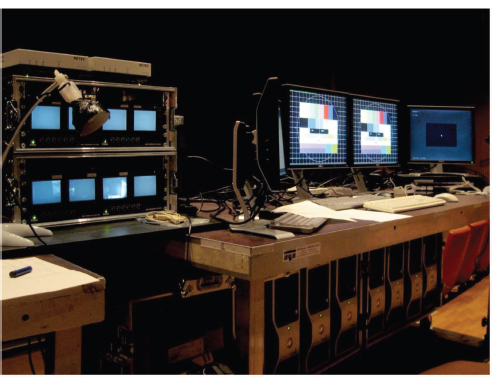

“Le Sacre du Printemps” premiered in 2006 at the Brucknerfest in Linz with an absolutely outstanding setup of computers and a 3D real-time digital environment, featuring a live performer on stage who represents the “chosen one” interpreted by dancer Julia Mach, in a new and challenging representation of the battle between the real and the digital. In this piece, we can see the representation of the “fear of humans creating new technologies which, in the end, are perceived by them as a threat”, like Obermaier says.

The performance involved the use of 3D glasses for the visualisation of stereoscopic projections, and the setup was something completely new and experimental. Once again, Obermaier was ahead of his time: his version of Le Sacre du Printemps marked an unprecedented turning point in the field of the performing arts and in the use of real-time 3D technology.

Interview

The following interview with Klaus Obermaier took place at his home in Vienna in September 2025. It was conducted as an extended conversation about his intermedia dance performances and included a series of questions concerning his main dance performances including “the concept of (here and now)”, aimed at retracing the experience from a conceptual and academic point of view.

CB: How did the opportunity to work on “Le Sacre du Printemps” arise?

KO: At the time, I had been experimenting extensively with 3D spaces since 2000, when we created a 3D laser show in Linz for the first time. Some years later, while I was considering developing a 3D stereoscopic performance, I was asked to create a piece based on Le Sacre du Printemps. Suddenly, I realised that I already had both a theme and a solution for it: the kind of stage I had been envisioning, using 3D cameras and tracking systems for the dancer, was perfect for reflecting on the sacrifice of a human being to nature from a contemporary point of view, shifting the meaning toward the sacrifice of the real in favor of the digital (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Klaus Obermaier. 2006. Le sacre du printemps. The technological set.

Looking back at this performance almost twenty years later, we can say that we are facing a similar issue today with AI - the fear that new technologies might strip away our sense of reality and, perhaps, even our humanity. In this piece, the “trick” is made completely visible: you can clearly perceive both fact and fake, as they belong to the same space. You see what the dancer is actually doing on the real stage - what it means to be human - and, simultaneously, what unfolds on the virtual stage she creates in real time, where she becomes progressively less human. She performs impossible movements with her arms and legs until she eventually dissolves into letters, symbols, and, finally, pixels. Another difference from the previous version was about involving the audience not only with the 3D vision, but also using one only dancer who is confronting herself, not with a mass of other dancers on stage but with the audience in the theatre. Thanks to the 3d technology you had a closeness and intimacy to the performer which you would never have in a normal performance. So, she was literally dancing for and against any single spectator which is not just watching but is in it and this was the big difference of creating a 3d virtual performance, but as an augmented reality that keeps together the real and the virtual. This was one of the main reasons why I went into interactivity, because it was the way to put all these things together: choreography, space, intimacy, virtuality and music.

Through this trajectory, another piece called “The concept of (here and now) takes shape as a condensation of the experimental techniques developed by Klaus Obermaier over nearly twenty years, unfolding across a series of chapters in which the techniques themselves emerge - but also what, at this point, begins to take the form of a language: not simply an aesthetic language, but above all a methodological language.

“The concept of (here and now)” is a work that in fact began as a teaching syllabus for a three-month course organized in collaboration between the Theatre Faculty of IUAV University of Venice and the Accademia Nazionale di Danza in Rome. The exchange program provided that, for the first two months, a selected group of students from the Academy would attend Obermaier’s course in Venice. During the final month, the group of theatre students travelled to Rome for an intensive workshop held at the Ruskaja Theatre of the Rome Academy. Guided by Klaus Obermaier, with the assistance of the author, the workshop culminated in a five-chapter performance as a final presentation of the students’ intensive course and premiered in Rome in 2010.

The three-month course was organised through a list of small ideas that Obermaier never developed fully and with the plan to use a very simple technology stage set. This situation led to a collaborative creation with the students’ contribution and the occasion was to try to conduct the group of students to freely experiment with this set of ideas and tools and see where they could get to. The result was quite a surprise.

Less than a year later, following two presentations at light festivals, the University of Erlangen - which regularly hosts the Figurentheater-Festival - promoted a new intensive workshop with other students, with the idea to further develop the performance within the Experimentiertheater, where the piece was completed with two more chapters to reach a 45-minute version.

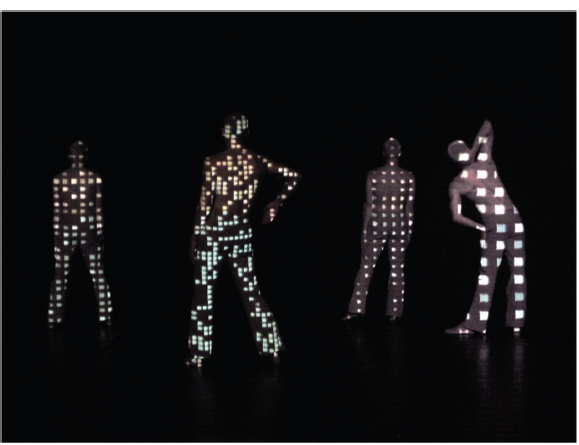

The seven-chapter performance premiered at the Figurentheater-Festival in 2011, marking the beginning of a three-year European tour. (Figure 7) Conceived and developed entirely within an academic environment, it involved no professional dancers or programmers. It is perhaps in this project that Obermaier most clearly applied what O’Dwyer (2021) defines as “practice-as-research”: the opportunity to explore in depth simple computer-vision techniques and to work with a very minimal technical rider led to something totally unexpected.

Figure 7: Klaus Obermaier. 2010. The concept of (here and now).

This piece stages a creative process that evolves through the exploration of new technologies, delving into paths already traced yet clearly not exhausted. In this case - perhaps determined by the specific context in which it was developed - Obermaier focuses more closely on certain techniques, simplifying the technology as much as possible while once again playing on the principles of integration of the elements on the stage and the intermedial artistic creation.

CB: The first question about the piece “The concept of…here and now” is about the title. Can you explain the meaning?

KO: In explaining this piece, I usually quote a statement by Daniel Charles, an important philosopher of music who was among the first to introduce concepts such as music as an “event”. In his words, “Performance does not happen in time, it creates its own time; it does not happen in space, it creates its own space.” This quotation aptly expresses what was taking place in that period of my artistic production.

“The concept of … (here and now)” consists of seven chapters that reflect and investigate these multiple simultaneous perspectives and the resulting ambiguity.

The transmission of body-time into computer-time and its retransfer into the physical space as visual and acoustic components of the digital environment, as well as the superimposition of different variable structures and timings, all this unveils the tension between reality and representation, between live performance and its digital depiction and transformation. And since all content is created in real-time by the performers, it shows us the fascination but also the limitations of our existence in the inescapable here and now.

CB: What role did the fact that this production took place primarily in an academic context play? In what ways did it influence the production process?

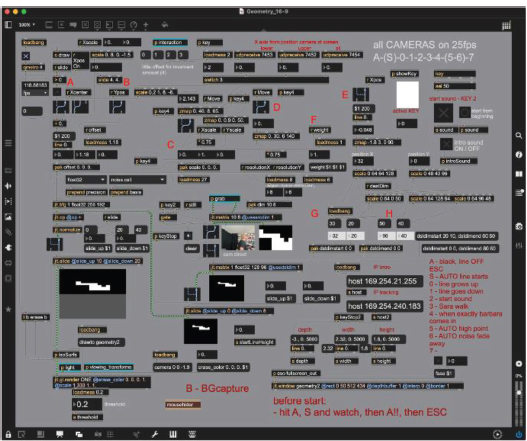

KO: Usually, when I’m teaching at university, I try first of all to explain to the students that they should start with simple ideas. After a quick crash course in the digital software I use the most, such as MAX/MSP/Jitter, (Figure 8) I ask them to explore the software and, as soon as possible, to begin setting up the “stage” and experimenting with the possibilities of the tools.

Figure 8. A Sketch of the Max/Msp/Jitter software for the performance.

At that time, I was teaching a lot, and in Venice we had a rather unique opportunity to spend an extended period freely exploring, making attempts, testing, improvising, with a system based on a very low-cost setup: a few laptops, a couple of projectors, and a pair of small HD cameras. After that, we concluded the course with a one-month residency at the small Ruskaja Theatre inside the Accademia Nazionale di Danza in Rome.

The most interesting thing that happened on that occasion was seeing the students take over the tools and use them in their own unexpected ways, giving ideas and learning to play.

For me, teaching has always been about that: finding a way to light the spark in their minds and then seeing how they can surprise you. And this is possible only through doing, not by talking or trying to explain.

CB: Was there a moment or a particular reason in your artistic career when you began to think about a production in which your role as an artist would encompass all aspects of the performance like concept, artistic direction, choreography, visuals, and music?

KO: The main reason is the circumstances. Usually, when I start thinking about a new piece, I try to collaborate with people who can do what I cannot, for example, sophisticated technology that requires programming skills. If I don’t have that knowledge, I need to ask programmers for help. In the end, I’m the one making the decisions, providing the ideas, and defining what should be done.

In my earlier works, when I was collaborating with choreographers, I reached a point where I felt I had enough knowledge to do it myself and to have full control over the process, to really go where I wanted to go without compromise. Every collaboration is a compromise, sometimes more, sometimes less.

For example, with DOPE in 2014, (Figure 9) it was easy for me to handle everything: besides the dance, I could design the piece, decide how to use the space, choreograph the movement, and of course compose the music. In that piece, actually, the music, with a very unusual rhythm, was the starting point that generated everything else. But that was just a coincidence and doesn’t mean I wouldn’t collaborate again with other artists.

Figure 9: Klaus Obermaier. 2014. DOPE.

CB: Many of your works have been pioneering in the use of real-time video and interactivity through computer vision and infrared cameras. You have consistently sought out the most advanced technologies and systems available, striving to harness them to their fullest potential. Today, with the advent of artificial intelligence, how do you envision the possibilities of performative art evolving?

KO: This is partially true. I very often used very sophisticated new technologies and sometimes we had to develop them completely, like in “Apparition” and in “Le sacre du printemps”, but very often I use very simple technology. It’s much more about the idea. If you need to push the limit, you have to push the limit. But if you have a great idea, already with well-known technology you can still push the boundaries and the possibilities, like in Dope, where for example there is nothing, just three video projectors as a smart source of light, but what matters is how to use it. For me this “how” is always the biggest question, how cleverly you use it. That’s probably the most important aspect, the cleverness, the sophistication in it, that’s what I’m searching for.I started to use these “dancing lights”, white light video projections on the body in dialogue with the background rear projection, in the final part of Vivisector. I then developed this idea further in The Concept of (Here and Now) and fully realised its most advanced version in Dope, (Lindinger, C. 2013) where the music provided the perfect rhythm for the piece. This is what I mean when I say that a concept is always a starting point, one that can lead to a wide range of possibilities and variations.

If I were a young student now, I would definitely engage with AI without any doubt. It is clear that one must be aware of the possibilities available out there. I was never interested, for example, in VR headsets because they did not give me the sense of liveness that I value so much, the strong feeling of the reality surrounding me. But that does not mean that someone else should not use them and explore their potential.

I am sure there are many ways to use AI in live performances. I would even have some ideas myself if I were working in performance again. Imagine, for instance, that you could say sentences on stage and they would be translated into something happening in real time. That is already quite an amazing possibility. You could even translate movements into other forms that generate something live on stage. I am sure there are already many such possibilities, and I would definitely explore them.

Many people are afraid of new tools. Today many say that AI is dangerous, but I remember when I created D.A.V.E., Vivisector and even more so Apparition, choreographers told me “You are killing dance, you are killing our work,” and now they are all using it.

So, I would say that everything is possible. AI is simply another tool, although it may also change everything completely. During one of my last conferences in Goa, India, someone in the audience asked me “Are you not afraid of being trapped in technology?” My answer was “Work with real people on stage. It is clear that if you sit in front of a computer with no interaction with the real world, you might be trapped. But if you communicate with real people on stage, it is a completely different thing.”

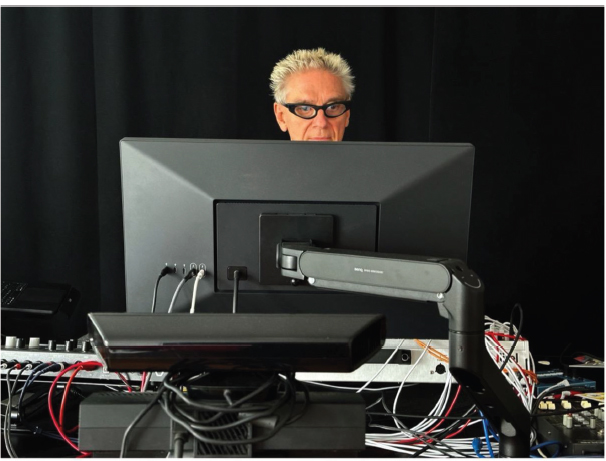

This is why I use interactivity so often. The moment you introduce interactivity, a dialogue begins between technology and human beings, and this dialogue is what interests me most. It is also what could attract me to AI. In the future I do not want to work on large projects anymore, but I can imagine using it in one of my pieces, where I am on stage as an audiovisual performer, employing it as a real-time tool. In the end, the question is not whether we should use future technologies in art, but how we will use them. (Figure 10)

Figure 10: Klaus Obermaier at his work desk, September 2025.

Results and conclusions

As Néill O’Dwyer (2015) observes, Klaus Obermaier’s Apparition (2004) embodies Stiegler’s conception of technology as capable of generating new forms of relation between body, image, and machine. According to O’Dwyer, the performance enacts on stage a symbiosis between dancer and computational system that visually coexist within a process of reciprocal transformation. In this sense, Apparition on the one hand, exposes the dimension of control and surveillance inherent in digital tracking technologies; on the other, it reveals their regenerative and creative potential, as tools capable of expanding the psychic and cognitive sphere of the subject.

In the chapter “Innovations in Motion-Tracking and Projection-Mapping: Klaus Obermaier” (in Digital Scenography, 2022), Néill O’Dwyer analyzes three key works in Obermaier’s career, D.A.V.E. (1999), Vivisector (2002), and Apparition (2004), as a true research trilogy marking the evolution of contemporary digital scenography.

From his early experiments with static projections on the body to the full interactivity of Apparition, Obermaier develops a language that transforms the performer into a surface, an interface, and a partner of the machine. While D.A.V.E. explores the theme of the digital double and post-human identity, and Vivisector delves into visual perception and bodily fragmentation through light, Apparition represents the turning point: the introduction of real-time motion tracking allows for genuine reciprocity between body and projected environment. As O’Dwyer notes, technology here is no longer a mere decorative element but a true scenic co-agent, shaping a “symbiotic ecosystem” between the human and the non-human.

The further experiences of Le sacred du Printemps, explored 3D stereoscopic spaces but also focused more on revealing the inner mechanism of the technological machine, as a kind of statement of the two faces of the digitalisation process. The concept of, on the other hand, because of the different nature of the production, led mainly to a theoretical reflection on creativity and the pedagogical processes, involved also in collective artistic creation.

What emerges, however, from Obermaier’s theoretical reflections and from his long and intense academic experience is precisely the fact that it is throughout the critical exploration of the tools, within the tools that he can become more aware of what is dangerous and what is a potential to explore.

Rather than defining his work as the creation of an aesthetic language, it would be more accurate to say that Obermaier has developed a “methodological and procedural language”, emerging from the continuous interplay between artistic research and teaching experience. This convergence has generated an operative trajectory within his artistic practice, allowing him to freely explore diverse territories without aesthetic limitations and maintaining a coherent conceptual framework.

References

de Lahunta, S. (2008). Blurring the boundaries: Intermedia performance and the body in digital space. In: C. Sommerer, L. Mignonneau, & D. King (Eds.). Interface cultures: Artistic aspects of interaction (pp. 225–227). Transcript Verlag.

Lindinger, C. (2013). The (St)Age of Participation: Audience Involvement in Media-Performance. Performance Research, 18(4), 123–133.

Mocan, R. (2013). Klaus Obermaier: “My work is not simply visualization…”. Ekphrasis: Images, Cinema, Theatre, Media, 10(2), 250–262. https://www.ekphrasisjournal.ro

Obermaier, K. (2008). Interactivity in stage performances. In: C. Sommerer, L. Mignonneau, & D. King (Eds.). Interface cultures: Artistic aspects of interaction (pp. 257–264). Transcript Verlag.

O’Dwyer, N. (2015). The cultural critique of Bernard Stiegler: Reflecting on the computational performances of Klaus Obermaier. In: M. Causey, E. Meehan, & N. O’Dwyer (Eds.). The performing subject in the space of technology: Through the virtual, towards the real (pp. 34–52). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137438164_3

O’Dwyer, N. (2021). Innovations in Motion-Tracking and Projection-Mapping: Klaus Obermaier. In: Digital Scenography: 30 Years of Experimentation and Innovation in Performance and Interactive Media (pp. 79–103). Bloomsbury / Methuen Drama

All images are courtesy of Klaus Obermaier

BIO

Cristina Barbiani  is an architect and PhD from IUAV University of Venice. She studied at New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston. She has collaborated with international artists and choreographers. She is the director of the Master in Digital Exhibit at IUAV, and her work focuses on digital exhibition design, video mapping and multimedia design. barbiani@iuav.it

is an architect and PhD from IUAV University of Venice. She studied at New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston. She has collaborated with international artists and choreographers. She is the director of the Master in Digital Exhibit at IUAV, and her work focuses on digital exhibition design, video mapping and multimedia design. barbiani@iuav.it